Category: Uncategorized

The Olympics of Court Reporting

Depositions are critical moments in legal cases where attorneys gather sworn testimony from witnesses. A deposition is typically conducted under oath, and the answers given will be used in court. While many depositions occur in a language that everyone involved understands, it’s important to note that language barriers can arise. In such cases, interpreters become indispensable in ensuring that all parties involved understand each other.

If you’re preparing for a deposition where an interpreter will be present, it’s crucial to understand how to effectively use their services. Here’s a detailed guide on how to use an interpreter during a deposition:

1. Understand the Role of the Interpreter

First and foremost, it’s important to understand what the interpreter’s role is and what they are not. An interpreter’s job is to facilitate communication between individuals who do not speak the same language, without adding their own opinions, interpretations, or judgments. They will translate spoken words, but they will not offer explanations or clarify terms. The interpreter must remain impartial throughout the deposition.

- Interpreter’s Role: To translate questions and answers accurately.

- What They Don’t Do: Provide legal advice, interpret non-verbal cues, or offer clarifications on content.

2. Ensure the Interpreter is Certified and Qualified

To ensure that the deposition runs smoothly, it’s essential to use a qualified interpreter. Legal settings often require certified interpreters who understand legal terminology and can provide accurate translations under oath. Check if the interpreter has experience with depositions or legal terminology in the relevant language.

Key considerations:

- Certification: Ensure the interpreter is certified by a recognized institution, such as the American Translators Association (ATA) or another accrediting body.

- Experience in Legal Settings: Legal deposition work involves specific terminology and phrasing, so using someone experienced in legal interpretation is crucial.

3. Pre-Deposition Briefing with the Interpreter

Before the deposition begins, schedule a meeting with the interpreter to discuss the specifics of the case and the terms that may arise during the questioning. This ensures the interpreter understands the context, and it can help them familiarize themselves with any technical or legal jargon.

During this meeting:

- Go over key terms that are specific to your case.

- Provide background on any specialized language or jargon that might arise.

- Discuss the style and tone you want to maintain in the testimony.

This preparation will improve the accuracy and efficiency of the interpretation process.

4. Speak Clearly and Slowly

When it’s time for the deposition to begin, it’s important to adjust your communication to accommodate the interpreter. Speak clearly and at a moderate pace. This will give the interpreter time to accurately translate each question and answer. Avoid speaking in long, complex sentences, as this can make interpretation more difficult.

- Keep Sentences Short: Shorter sentences help the interpreter maintain accuracy.

- Avoid Slang or Idioms: Idiomatic expressions may not translate well into another language, so it’s better to use straightforward language.

5. Allow Time for Translation

In any deposition with an interpreter, you need to allow extra time for the translation process. A simple question or response will take longer to be interpreted because both the question and answer must be translated. Be patient, and don’t rush through the questioning.

A good rule of thumb is:

- Pause After Each Question: Give the interpreter time to translate before the witness answers.

- Pause After Each Answer: Allow the interpreter time to translate the response back into the language of the questioner.

6. Clarify if There Are Any Issues with Translation

If something seems unclear or the interpreter has difficulty translating a response, it’s important to address the issue immediately. Misunderstandings or errors in translation could lead to incorrect testimony or confusion in the deposition process. If you feel that something was lost in translation, don’t hesitate to ask for clarification.

- Pause if Needed: If there’s confusion or doubt about the translation, stop the questioning and ask the interpreter to clarify.

- Check for Accuracy: After a response, ask if the interpretation was accurate, especially if something seems off.

7. Respect Cultural Sensitivities

During a deposition involving an interpreter, it’s also essential to respect cultural sensitivities. In some cultures, certain body language or gestures may be interpreted differently, which can impact how a witness or deponent responds to questions.

Be mindful of these aspects:

- Maintain Professionalism: Always address the interpreter and witness with respect.

- Cultural Awareness: Be sensitive to how different cultural norms may affect communication and understanding.

8. Have a Contingency Plan for Technical Issues

In cases where the deposition is being held remotely, ensure that technical issues such as audio or video glitches won’t disrupt the process. When working with an interpreter in a virtual setting, both the interpreter and participants should have access to the necessary technology to ensure the translation is clear and accurate.

Tips to avoid technical issues:

- Test Equipment in Advance: Make sure the interpreter’s audio and video setup works properly before the deposition starts.

- Ensure a Stable Connection: Ensure that both the interpreter and deponent have a reliable internet connection to avoid disruptions.

9. Record the Deposition Properly

If the deposition is being recorded, make sure that the interpreter’s translations are also being captured. This is particularly important if there’s a need for a transcript to be produced later. In some cases, the interpreter may need to be sworn in separately before the deposition starts, just like the witness.

- Transcript Accuracy: Ensure the court reporter or transcriptionist is aware of the interpreter’s presence and role in the deposition.

- Interpreter’s Oath: The interpreter must be sworn in, confirming their impartiality and commitment to providing accurate translations.

10. Review Testimony Carefully

After the deposition, take time to review the translated testimony thoroughly. Pay close attention to the details and ensure that no misunderstandings or errors occurred during the translation process. If any issues arise, you may need to address them before proceeding to trial or further legal proceedings.

Conclusion

Using an interpreter during a deposition requires careful planning, patience, and understanding. It’s essential to ensure that the interpreter is qualified, clear on legal terminology, and aware of the deposition’s specifics. By following the guidelines above, you can help facilitate a smooth, accurate, and fair deposition process, ensuring that all parties have the information they need to proceed with the case.

Always keep in mind that the integrity of the testimony relies heavily on the clarity of communication, and an interpreter plays a vital role in maintaining that integrity across language barriers.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

NC Court Reporters can book your court reporter, conference room, and interpreter. We use only court-approved interpreters. Book now: https://courtreporternc.com/schedule-with-nc-court-reporter/

The Olympics of Court Reporting

A court reporter’s skill set can be used for numerous purposes other than capturing the record in a courtroom or in a deposition. Members of the Texas Court Reporters Association are among the court reporters nationwide who volunteer their specialized skills to ensure that the stories of our country’s veterans are preserved for future generations.

The Veterans History Project, a part of the Library of Congress, started in 2000 and collects histories from any veteran who served from World War I through the Iraq war. Lorie Schnoor, President of the Texas Court Reporters Association, said that once a veteran has contacted them and is willing to share their story, arrangements are made for a 30-minute interview. A trained interviewer talks with the veteran while the court reporter takes down the record. The court reporter then prepares a verbatim transcript, which is submitted to the Library of Congress.

“Nationwide … over 4,000, I guess, transcripts have been done by court reporters,” Schnoor said.

Schnoor admitted it’s hard to get the word out about the project. She said the TCRA has put up flyers in businesses and places that veterans frequent, but getting veterans to come forward is the hardest part.

“We don’t want to track them down and, you know, ‘Please do this for us,’ you know?” Schnoor said. “It’s got to be on their own free will.”

She added many veterans they come in contact with don’t want to relive the experience they had while in the Armed Forces.

Due to a shortage of court reporters in Texas and nationwide, it sometimes takes a while to get an interview scheduled. The interviewers and court reporters prioritize older veterans, particularly World War II veterans, since their numbers are quickly dwindling.

For more information on how you can participate in this vital program, either as a court reporter or an interviewer, visit the Veterans History Project website: https://www.loc.gov/vets/.

The Olympics of Court Reporting

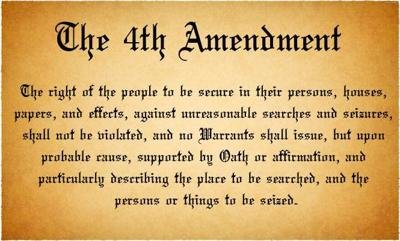

An official court reporter in Indiana recently found herself in a different position in the courtroom and fighting for her Fourth Amendment right against warrantless seizure and other constitutional rights.

Howard County court reporter Rachel Roberts is facing three felony theft charges, with prosecutors alleging that she overcharged thousands of dollars for court transcripts. Official court reporters are paid a salary for their work inside the courtroom. When a party orders a transcript of a trial or hearing, the court reporter is paid separately, since those transcripts must be prepared outside of their working hours in the courtroom for the most part. How that pay is calculated varies by jurisdiction. Some states set the transcript rate for all cases, and others only set the rate for indigent criminal cases and allow the reporters to charge market rates for other types of transcripts.

In Roberts’ case, an investigation began in 2015 when Judge William Menges (who is also Roberts’ uncle) and the county auditor noticed discrepancies in her billings. That investigation purportedly showed that “Roberts earned nearly $10,000 more for transcriptions in three cases than was allowed by law,” leading to the three felony charges filed in May 2017.

In September Roberts’ attorney moved to suppress evidence in the case, claiming investigators, in executing multiple search warrants in early 2015, seized various pieces of evidence not covered in the warrants. According to the motion to suppress, investigators obtained copies of Roberts’ bank records even though a warrant or subpoena wasn’t issued for the records.

As such, her attorney deemed that seizure as “warrantless,” violating her Fourth Amendment rights.

In addition, Roberts’ attorney alleges that investigators “elicited various statements” from her without properly informing her of her Miranda rights and that the warrants signed by Judge Menges were not valid because his role in initiating the investigation leading to the charges meant he was not a “neutral and detached magistrate” and because he will likely be a witness at trial.

[Judge Matthew] Kincaid concurred, writing in an order that he found that searches of Roberts’ home and office “violated the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution and were unreasonable under totality of the circumstances.” He ruled that “all items seized and all observations and statements made during or as a result of the execution of the warrant are suppressed and may not be presented to the jury at trial.”

Prosecutors also planned to introduce evidence at trial showing “acts of ‘ghost employment’ and acts of ‘overbilling’ in cases not relating to the charges Roberts faces.” Roberts’ attorney argued in the same motion that such evidence “would unfairly prejudice or mislead the jury,” and Judge Kincaid ruled in Roberts’ favor on that issue as well.

The case is set for trial in February, 2020.

The Olympics of Court Reporting

When a courtroom drama is shown on television or in the movies, the most inconspicuous person in the scene is the court reporter. Most people don’t notice the silent guardian of the record, and if they do, they generally don’t know or understand what they do. Since a nationwide shortage of court reporters has been disrupting court and deposition proceedings for a number of years, everyone in the legal field is feeling their absence.

The Wall Street Journal recently wrote about this “Silent Problem Facing the Nation’s Courtrooms” and its consequences.

“A few months ago, when court reporter Shari Krieger,48 years old, got sick, she called several firms to find a replacement. When no one was available, the judge had to reschedule the entire day. ‘Everybody was there, ready to go,’ said Ms. Krieger, who works in the Fort Worth, Texas, area. ‘To know that nothing can happen without you—that’s a big responsibility.'”

In 2015, Bureau of Labor Statistics data indicated that there were 17,700 court reporters in the United States. In May 2018 that number had declined by approximately 18 percent, down to 14,500. As older court reporters have retired, there haven’t been enough new court reporters to take their place, likely due to in part to the fact that the profession isn’t very well known.

Gaining the speed necessary to graduate from a traditional court reporting school can take a number of years, and then the student must pass a certification test before they’re legally able to work in many states. In some states, such as California, the percentage of students who pass the certification exam is extremely low. For example, only six out of 111 people who sat for California’s March 2019 certification exam passed. California also has one of the most extreme court reporter shortages.

Out of desperation, some attorneys and court systems have attempted to rely on unmonitored digital recording devices to record a hearing or a deposition and then hire a transcription company to produce a “verbatim” transcript. This has sometimes had disastrous results when there is an equipment malfunction, background noise, a mumbling witness, or when the participants all speak at the same time. And, an in-courtroom court reporter is required for most serious criminal cases.

Fortunately, electronic court reporters are becoming more prevalent and accepted by attorneys and judges alike. Electronic reporters use specialized software and high-quality audio-visual equipment to record testimony. The software allows them to record each speaker’s audio feed on a separate track to ensure complete accuracy of the transcript. They also take contemporaneous notes of the proceedings within the software, which are then linked to that spot in the audio record. An electronic court reporting student can complete their training and certification in a fraction of the amount of time it takes a traditional student to do the same, and with an exponentially higher success rate.

Hopefully, courtroom administrators, licensing boards, and attorneys will continue to make way for innovative ways to solve the court reporter shortage.

For all of your court reporting needs in North Carolina, please call on NC Court Reporter. We have experienced professionals here to serve you. It’s easy to schedule online.

In you need help deciding exactly what services you require, our scheduling team is ready to assist you: 910-777-5375.

The Olympics of Court Reporting

It’s one of the things we all know we should do regularly, but very few of us actually follow through – backing up the data on our computers. For most people, losing a hard drive they hadn’t backed up would be a major inconvenience (or heartbreaking if family photos were lost), but the stakes are much higher when a court reporter loses all of their computer files.

Court reporters, no matter the method, store their notes and audio files electronically. Freelance reporters almost always prepare a transcript within weeks after the date of a deposition, and once the official certified transcript is prepared the original notes and audio files are less important.

Official court reporters, or courtroom-based court reporters, only prepare a transcript when one party places an order. In some criminal cases, such as murder trials, a transcript order could cover hearings taken years earlier that were never transcribed. If those files were destroyed in a hard drive crash, appellate courts wouldn’t have a complete and accurate record upon which to base their ruling. That could lead to the appellate court ordering an entirely new trial, from start to finish.

An appellate court in Texas is facing just such a dilemma. John Feit, a former priest who is now 86 years old, was convicted in 2017 of murdering one of his parishioners decades ago. He appealed the conviction, and the trial judge ordered the court reporter to prepare a transcript of all of the proceedings in the case, including pre-trial hearings held in 2016.

Unfortunately, those records “were lost after the hard drive belonging to [Julian] Alderette, [Judge Luis] Singleterry’s court reporter, ‘was dropped and damaged,’ according to an affidavit Alderette filed. As a result, Alderette was unable to provide the appeals court with a transcript of any 2016 hearings from Feit’s case.”

Feit’s appellate counsel, O. Rene Flores, has been unable to prepare a brief for the Court of Appeals presenting his case for reversing Feit’s conviction because he doesn’t have access to these transcripts. Hearings are ongoing before the trial judge to determine how to proceed. Hidalgo County District Attorney Ricardo Rodriguez, Jr. said he “‘feels confident'” prosecutors and Flores ‘will be able to agree and make a record of whatever hasn’t been turned over to the court of appeals.’ That would likely entail recreating a transcript of all 2016 hearings, which include Feit’s arraignment and three pre-trial hearings.”

Official court reporters are subject to records retention requirements promulgated by each state or by the federal government, depending upon the system in which they practice. Records of official court reporters are considered property of the court, not the court reporter. It’s unclear where the process broke down in the case of Judge Singleterry’s courtroom, but one thing that’s exceedingly clear is how important it is that court reporters, regardless of what records retention requirements they’re subject to, must be conscientious about backing up their notes. The lives and livelihoods of their fellow citizens depend on it.

The Olympics of Court Reporting

Mounting student loan debt is a major issue among millennials, who sometimes spend close to $100,000 obtaining a four-year degree then find themselves unable to find jobs where their paycheck covers both their student loan payment and living expenses. Increasingly, students are turning to trade schools so they can receive career training at a fraction of the cost.

One trade school option that’s sometimes overlooked is court reporting school. To be a successful court reporter above-average written language skills are required, but a university degree is not. In contrast to a traditional college degree, court reporting schools have almost a 100 percent placement rate (according to a recent Forbes article) court reporting students graduate in two years instead of four, and with less than $20,000 in debt on average.

Depending on the method of court reporting the student chooses (different methods have different technology and equipment costs), though, the student could obtain a court reporting certification for far less.

That sounds like an attractive option for the right students.

In addition, there is a long-standing court reporting shortage across the country. In some areas, such as California, firms are offering large daily bonuses to court reporters to cover depositions. State court systems have also felt the pinch and had to cancel or delay sessions of court due to the shortage. One North Carolina county was forced to delay a major criminal trial because a court reporter wasn’t available.

So, how does one become a professional court reporter? There are few brick-and-mortar court reporting schools remaining, but many of the schools that remain offer an online option. This is good news for students who need to work full-time while attending school. North Carolina court reporters, including the team at Legal Media Experts, routinely mentor court reporting students in Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill. The students shadow the reporters during every stage of a deposition, from scheduling to deposition transcript production, to gain hands-on experience while they finish school.

We are always looking to add to our team of professional court reporters and legal videographers. If you’re a court reporting student looking to work in Wilmington, Raleigh, Durham, Charlotte, Greensboro, or Chapel Hill, we’d like to hear from you. Call our office at 910-777-5375 for more information.

The Olympics of Court Reporting

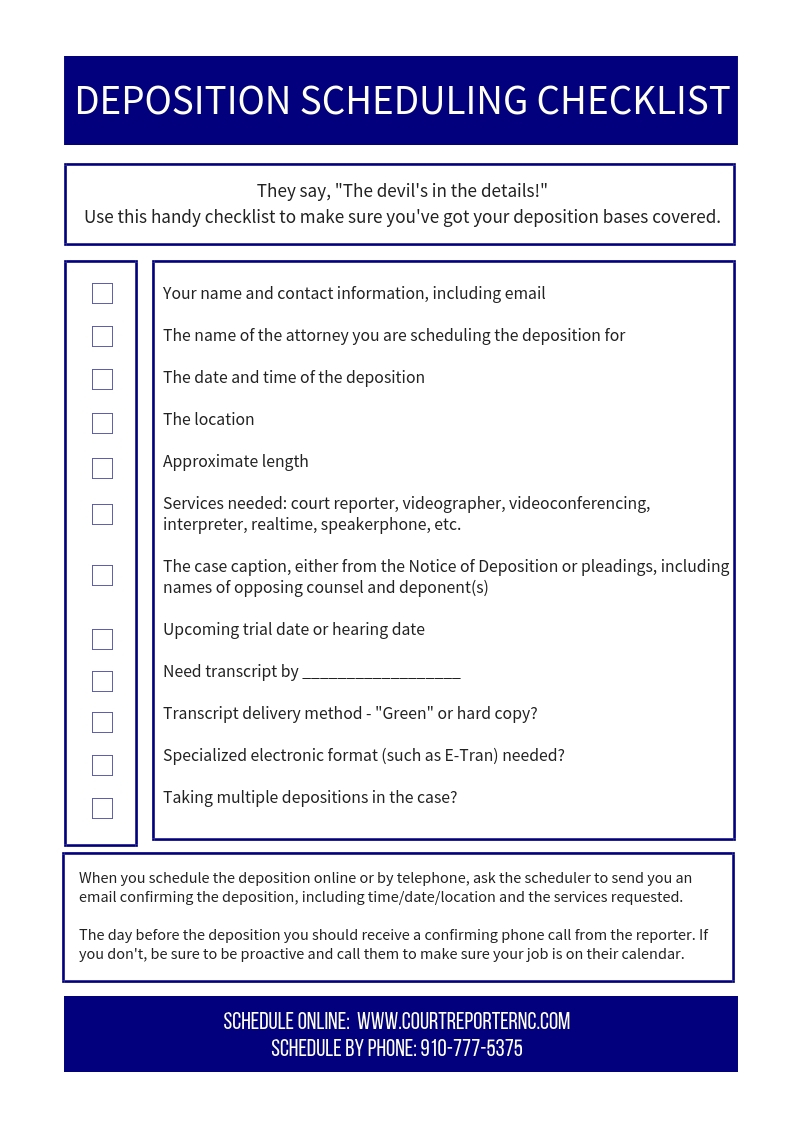

Scheduling a deposition is easy –

simply pick up the phone or send an email, right? But if your paralegal doesn’t

have all of the pertinent information, or if that information is not

communicated to the court reporting firm, you run the risk of getting into some

sticky, time-consuming, or expensive situations.

1. When and Where?

Obviously, the scheduler will need

to know the date, time, and location of the deposition or hearing. But, you

will probably also be asked what day of the week (to ensure that the day of

week and date match). In addition, if participants will be located in various

time zones, it’s helpful to list what the deposition start time is in each time

zone. For example: 12 noon Eastern, 11 a.m. Central, 10 a.m. Mountain, 9 a.m.

Pacific.

Before scheduling the deposition,

double-check the address and phone number of the location. If there is anything

unique about how to find the location (for instance, if the signage isn’t

readily visible from the road, or the building is tucked away in the back of an

office park), be sure to let them know. If the court reporter will be arriving

before the building’s regular operating hours, let them know if there are

special instructions for where to park.

2. How Long?

We understand that even the

attorneys can’t provide an accurate estimated length of the job, but they’ll

generally know ahead of time if they anticipate a deposition to last 30 minutes

or all day. The reporter will be there as long as is necessary (we’ve

definitely burned the midnight oil on a few occasions) but knowing an estimated

length will help us to assign the best reporter for the job. Our scheduling

department tracks which reporters have a transcript backlog, are leaving on

vacation soon, or have evening commitments, and these factors are taken into

consideration when scheduling.

3. Case Caption/Title

Email the reporter a copy of the

Notice of Deposition, or, if one isn’t available, a copy of a pleading or the

case caption, including the names and contact information of opposing counsel

and whom they represent. This is particularly important in a deposition taken

by video conference, so the reporter doesn’t have to go through gathering that

information from each participant at the time of the deposition.

If the case is technical or has

specialized vocabulary, emailing a copy of the pleadings ahead of time will be

a huge help for the court reporter.

4.Future Depositions

If you know you will be taking

multiple depositions in the same case, let the scheduling department know.

They’ll make every attempt to have the same reporter cover each deposition.

5.Special Services

Do you need a videographer? What

about an interpreter? Will you need a videoconference set up? Do you need to

use our conference room facilities? Be sure to let us know as soon as possible.

6.Standard or Expedited Delivery?

If you know you’ll need the

transcript sooner than our standard 10-12 business day turnaround, make sure to

let us know when you book. It’s even more crucial to let us know ahead of time

if you think (or know) you’ll need it overnight or within two or three business

days, because that will affect which reporter is assigned to cover the job.

7.Delivery mode

At NC Court

Reporter, we believe in being environmentally responsible. As such, we feature a

“Green Delivery” transcript package which includes a PDF version of

the full-size and condensed transcript (4 pages printed on one page), with

exhibits scanned, attached, and hyperlinked, and a TXT file. Hard copies of the

transcript and exhibits are available, though; please let the scheduler know if

you’ll need a hard copy (other than the original).

To schedule your next

deposition with NC Court Reporter, use our online scheduling tool or call

910-777-5375.

The Olympics of Court Reporting

Over the last few decades the number of practicing court

reporters across the country has steadily declined, leading to canceled court

sessions and, in some areas, difficulty finding enough court reporters to cover

depositions. Since court reporting can be a lucrative career, why is there a

shortage of reporters?

It’s true that the profession can be lucrative, and

freelance reporters have the added benefit of a somewhat flexible schedule.

But, court reporting is also physically demanding. Both

stenotype reporters and voice writers experience repetitive stress injuries and

back strain, and some are forced to retire early.

Also, the hours and pay can be wildly unpredictable. Though

freelance reporters can generally choose which assignments to accept, many work

more than 40 hours a week on a regular basis and don’t know what their exact

schedule will be from one week to the next. Because of this unpredictability,

every court reporter can tell you about the time they had to work through

Christmas, Thanksgiving, or other important days, or had work for 24 hours

straight in order to make the plane for a family vacation. (Usually this is due

to last-minute expedites or a deposition that was scheduled for one hour going

for eight hours – or both.)

Official reporters have the benefit of a steady salary and

benefits, but any transcripts ordered must be prepared outside of court time

and transcripts for indigent defendants are paid at a low rate set by the

courts.

In addition, for stenotype court reporting students

particularly, it’s difficult to achieve the typing speed and accuracy necessary

to pass certification exams.As a result, enrollment in traditional court

reporting schools has been down for decades, and many have closed entirely.

As existing court reporters retire, there are fewer and

fewer new traditional court reporters available to take their place.To address

this shortage some states cancel sessions of court when there is no reporter

available. Other states have chosen to outfit their courtrooms with electronic

recording systems operated by the courtroom clerk (sometimes with disastrous

results). When people’s lives, liberty, and property are on the line, neither

of those options are acceptable.

The best solution is to embrace electronic court reporting.

An electronic court reporter uses pecialized software and high-quality

audio-visual equipment to record testimony. The software allows them to record

each speaker’s audio feed on a separate track to ensure complete accuracy of

the transcript and to take contemporaneous notes of the proceedings within the

software, which are then linked to that spot in the audio record. Like their

stenotype and voice writer counterparts, electronic reporters pass

certification exams testing their knowledge of court and deposition procedure,

grammar and language competency, and ability to produce an accurate transcript.

They are also held to the same ethical and professional standards as other

court reporters.

When people are involved in civil or criminal litigation the

stakes are high. Litigants should not be forced to face long delays before they

have their day in court, and deserve a high-quality record to protect their

rights. Court administrators and court reporting firms should embrace

electronic court reporters to address the court reporter shortage.

The Olympics of Court Reporting

After a court reporter has completed their course of

training, they have the opportunity to sit for professional certification exams

offered by various court reporting associations. The organization through which

a reporter will seek certification depends upon their method of capturing the

record.

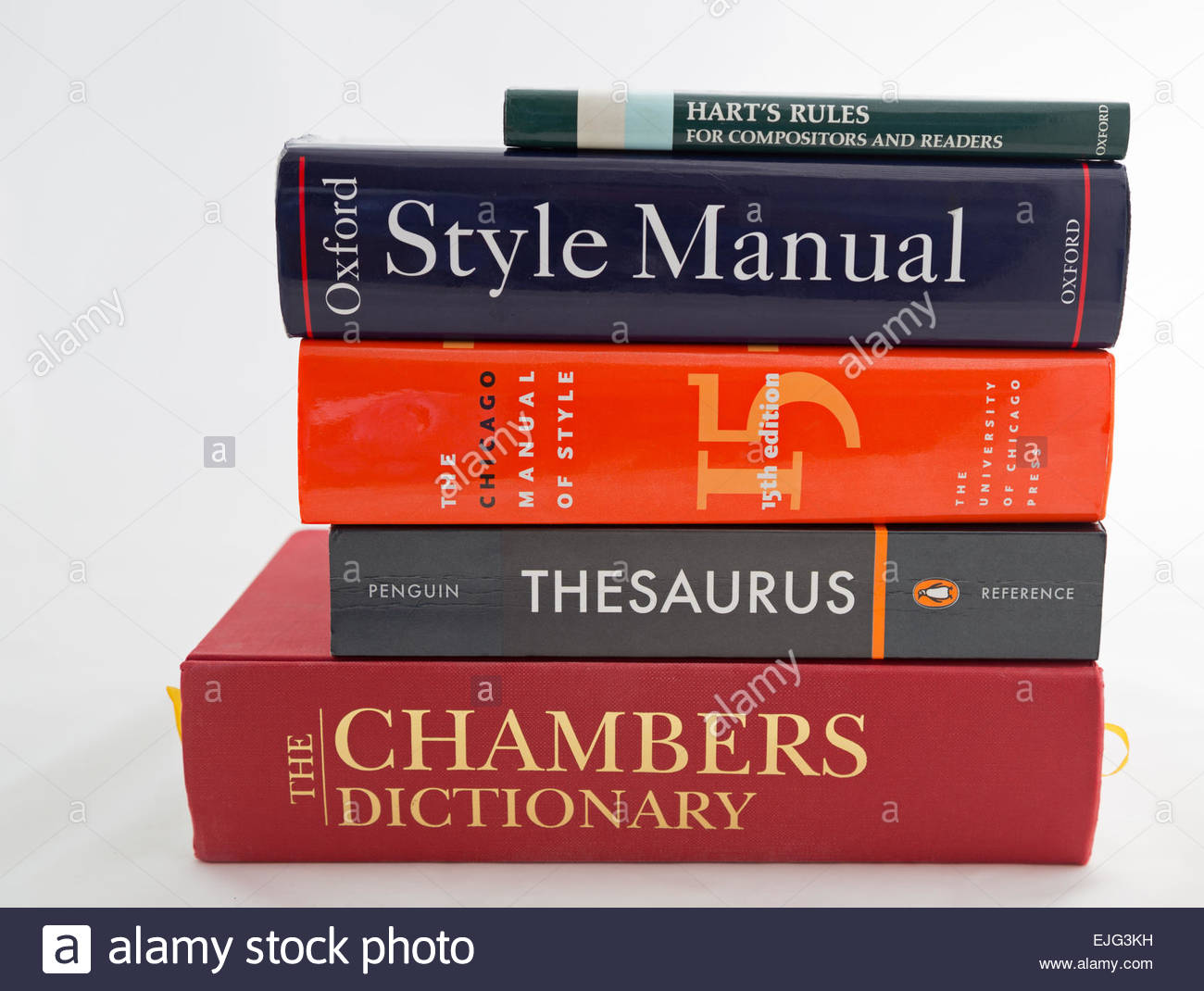

Each professional organization’s certification exams are

aimed at verifying that the court reporter has the necessary skills to record

the proceedings and produce an accurate, verbatim transcript. Preparing a

transcript is more complicated than simply getting the spoken words onto the

transcript page. Since many depositions contain medical or technical terms,

reporters must be familiar with medical and technical terminology, and must

have a command of grammar and punctuation.

In addition, each association requires continuing education

hours in order to retain certifications. Since technology is rapidly changing,

taking part in continuing education enables reporters to stay abreast of the

latest developments and any changes in best practices.

National Court

Reporters Association (NCRA) certifies stenotype

reporters, legal videographers, realtime captioners, and court reporter

instructors. There are three levels of certification for Registered court

reporters: Professional, Merit, and Diplomate. They also offer certification as

a Certified Realtime Reporter. Each certification requires that the candidate pass

a written knowledge test covering technology, reporting practices, and

professional practices. All certifications except Diplomate require candidates

to capture literary, jury charge, and question-and-answer dictations at various

speeds – up to 260 words per minute – then create a transcript with 95 percent

accuracy.

National Verbatim

Reporters Association (NVRA) certifies stenotype reporters, voice

writers, legal videographers, CART providers, broadcast captioners, legal

transcriptionists, and scopists. For court reporters, there are separate

certifications for military court reporters and realtime court reporters. Each

certification track has a basic certification and a Master certification. Court

reporter certification exams include a written knowledge test and a practical

exam, and are held at proctored test sites throughout the country. The written

knowledge test covers reporting the verbatim record, transcript production

including vocabulary and punctuation, transcript distribution, professional responsibilities,

and ethics. The practical exam includes three separate dictations literary,

jury charge, and question-and-answer, given at increasing speeds – up to 260

words per minute. Certification candidates must report the dictations using

either their stenotype or voice writing equipment then create a verbatim

transcript with 95 percent accuracy.

The American

Association of Electronic Reporters and Transcribers (AAERT) provides certificationfor

electronic (digital) reporters and transcribers. The Certified Electronic

Transcriber exam has two parts: an online knowledge test covering

transcript format and proofreading, general court procedures, and vocabulary,

and a practical examination in which the candidate is given an audio file

containing a mock court proceeding and must create a full transcript in Federal

Court format within 120 minutes, with 98 percent accuracy. The Certified

Electronic Reporter exam is taken online and consists of a knowledge test

covering court reporting and technical questions, general court procedures and

practices, vocabulary, and log annotations.

Becoming certified indicates that a court reporter takes

their professional duties seriously and are committed to staying at the

forefront of the industry.

The Olympics of Court Reporting

COURT REPORTING TERMINOLOGY

ASCII – (Pronounced “askee”) A computer term which stands for American

Standard Code for Information Interchange.

Ascii is a means of exchanging text among dissimilar computers and

computer programs.

CALENDAR – A

calendar in the field of law is the schedule of upcoming appearances in court

or a schedule of legal proceedings.

Attorneys keep a calendar of times when and where certain activities are

to take place, the same as a court reporter.

A job which is scheduled to be done is said to be “on

calendar.”

CAT –

Computer-Aided Transcription. CAT

systems are computer equipment and programs that perform three major functions:

First, they translate the reporter’s

notes into English. These notes then are

stored in electronic form. Secondly,

they provide an editing system that is highly specialized for court reporting

which allows the roughly translated text to be put into final transcript

form. Finally, the CAT system prints the

transcript in the format required by legal practice — numbered lines, double

spacing, and a box.

CIC – Computer-Integrated Courtroom. CIC is the application of computer technology

in a courtroom such that all parties present have immediate access to the text

of the proceedings as it happens, plus possibly other resources such as past

testimony.

CONDENSED

TRANSCRIPT – A miniaturized copy of the original transcript printed in such a

way as to place four pages of transcript on a single sheet of paper.

DEPONENT – A

person who testifies under oath. The

person answers questions put to him, and these questions and his answers are

recorded in shorthand by the court reporter.

DICTIONARY –

An essential part of a CAT system used in translating the reporter’s notes into

English. The dictionary contains

correlations between stenographic notes and English text. Since stenographers develop their own writing

style and system of abbreviations, dictionaries are specific to each individual

reporter and are built up through repeated use and correction of the reporter.

DEPOSITION –

The giving of testimony under oath. The

actual testimony of an individual or individuals. Depositions are usually distinguished from

courtroom testimony. Depositions are

taken before a case goes to trial, during the “discovery” phase of

the case.

EXHIBIT –

Document, object, etc., shown in court as evidence. Exhibits are marked with an identifying

number by the court reporter and then indexed and described in the transcript

of the proceedings.

EXPEDITE –

An expedite is a job that has been explicitly ordered by one of the attorneys

at a deposition to be delivered faster than normal in exchange for an increased

fee.

JOB – A term

used by court reporters to refer to one deposition.

LITIGATION

SUPPORT – Broadly, this refers to any of the tools that an attorney or

paralegal may use to help categorize and display information about the case —

things that support the litigation. In

court reporting, litigation support or lit support refers to the production of

the transcript in computerized form, such as an ASCII , eTranscript, condensed

transcript, and keyword indices.

NOTES – The

original stenographic marks made by a court reporter during the proceedings

being reported. The steno machine

records them in electronic form.

NOTICE – In a legal sense, a Notice is a formal

document prepared to inform all parties involved when a deposition is going to

occur and where

PARTY – A

person who takes part in the performance of any act, or who is directly

interested in any affair, contract, etc., who is actively concerned in the

prosecution or defense of any legal proceeding.

REALTIME –

Realtime as a computer term means “happening right now, in present

time.” This is where a court

reporter hooks her laptop computer up to the attorney’s laptop computer and

feeds them the testimony.

REPORTED –

Used as a noun, “reported” is a completed session of note taking by a

court reporter.

ROUGH-DRAFT

ASCII – A term that refers to the first, rough translation of the reporter’s

notes into English. Because the text has

not been edited and proofread by the court reporter, the reporter cannot

certify that the record is complete and correct.

SCOPING –

The process of editing the first, rough translation of the reporter’s notes

into final form. The scoped transcript

is then proofread by the reporter.

SCOPIST – A

person who assists a court reporter by taking the first, rough translation of

the reporter’s notes and editing them into full transcript format.

STENO –

Short for stenography. Steno can also

refer to the notes made by the court reporter.

STENO

MACHINE – A stenographic writer. A steno

machine has three banks of keys, plus a bar, which are stroked in combination

to produce marks that represent sounds, words, and phrases.

STIPULATION

– The name given to any agreement made between attorneys respecting business

before the Court. In a deposition, usual

stips (stipulations) are often asked for, which the attorneys should look at

what the court reporter has for usual stips, as each is a little different but

most say essentially the same thing.

STROKE – To

play the keys on a steno machine so as to produce stenographic marks. The keys are pressed using both hands. Each downward motion of the hands is a stroke

and the mark so produced is also sometimes referred to as a stroke.

TAKING

ATTORNEY – The attorney who ordered the deponent to appear for questioning.

TESTIMONY –

The statement or declaration of a witness under oath.

TRANSCRIPT –

The written copy of what occurred at a legal proceeding, produced by the court

reporter.

TRANSLATE

(to translate notes) – The stenographic notes taken by the reporter must be

translated into English text before they can be used by anyone else. It used to be that reporters read their notes

from the paper pad and typed the English directly. Nowadays, it is common to use a computer program

known as a CAT system to make a first pass at the translation. After the CAT system has translated the job,

it still need to be scoped and proofread.

UNTRANSLATES

– Untranslates are instances of untranslated stenographic markings appearing in

a work which has been translated from stenographic notes. Untranslates will be present in a transcript

which has been translated by not yet scoped, and some will appear in realtime

text during a deposition.

WRITER – A

steno machine.